What to do if you don't have a passion

TLDR: Build your personal flywheel

Googling “I don’t have a passion” results in half a billion links.

Half a billion. Think about that for a second.

This reminds me of the Star Wars scene where the planet Alderaan, home to two billion people, was destroyed. The character Obi-Wan, witnessing this, gravely remarks that he "felt a great disturbance...as if millions of voices cried out in terror."

As I witness people desperately seeking their passions, I hear their voices crying out in terror. This desperation is stoked by media, which serves us stories about how Mark Zuckerberg turned his passions for technology and business into worldwide fame and hundreds of billions of dollars.

There’re many flavours of the angst of being passionless. What if your passions aren’t lucrative? What if you don’t have a passion? What if you don’t even have hobbies?

Defining the Problem — and Untangling Yourself From It

The problem arises because we’re too fixated on the target. The overt focus on finding a “passion,” “zone of genius,” or “Personal Monopoly” stresses people out, and can actually inhibit the pursuit of a unique and meaningful path.

Despite what you’ve been told by the business media and well-meaning public intellectuals, you don’t need a grand vision. You don’t need to be architecting a set of complementary skills that will lead to endless riches.

And if you aren’t doing this architecting – if you don’t even know how to – there may not be anything wrong with you.

There is a way to melt away this tightness: observe yourself. This isn’t an iron prescription; you don’t need to install a camera in your shower. But pay attention to the rhythm of your days. Pay special attention to the set of habitual behavioural patterns that you participate in (or that beset you).

These patterns and habits must be inter-related. More importantly, they must reinforce themselves and each other, otherwise they’d fizzle out instead of repeating themselves over months and years. As they repeat, they gain an edge, crowding out other behaviours. In time, they may solidify into personality traits.

Flywheels

An interrelated set of behaviours that reinforce each other and lead to an edge…did someone say “flywheel”?

Flywheels have been around since the 11th century, but author Jim Collins applied them to business in his seminal book Good to Great. Collins defines flywheels as a group of actions that combine to lead to an accumulating advantage in a certain direction.

One famous example of a business flywheel is Amazon’s1, which describes how the company enjoyed small gains that fed off of each other until the company was unstoppable:

Remember those habit patterns I asked you to reflect on? These patterns can make up your own flywheel – the Flywheel of You – and you might not even realise it.

The thing about personal flywheels is that they’re imperfect. They won’t be a seamless synergy like Amazon’s. They’ll include habits and behaviours you’ve adopted to cope with your flaws.

That’s why detachment is so important. Without it, you’ll look too hard for rosy, LinkedIn-ready pieces of your flywheel, and miss what’s right under your nose.

Take writer Robert Greene.

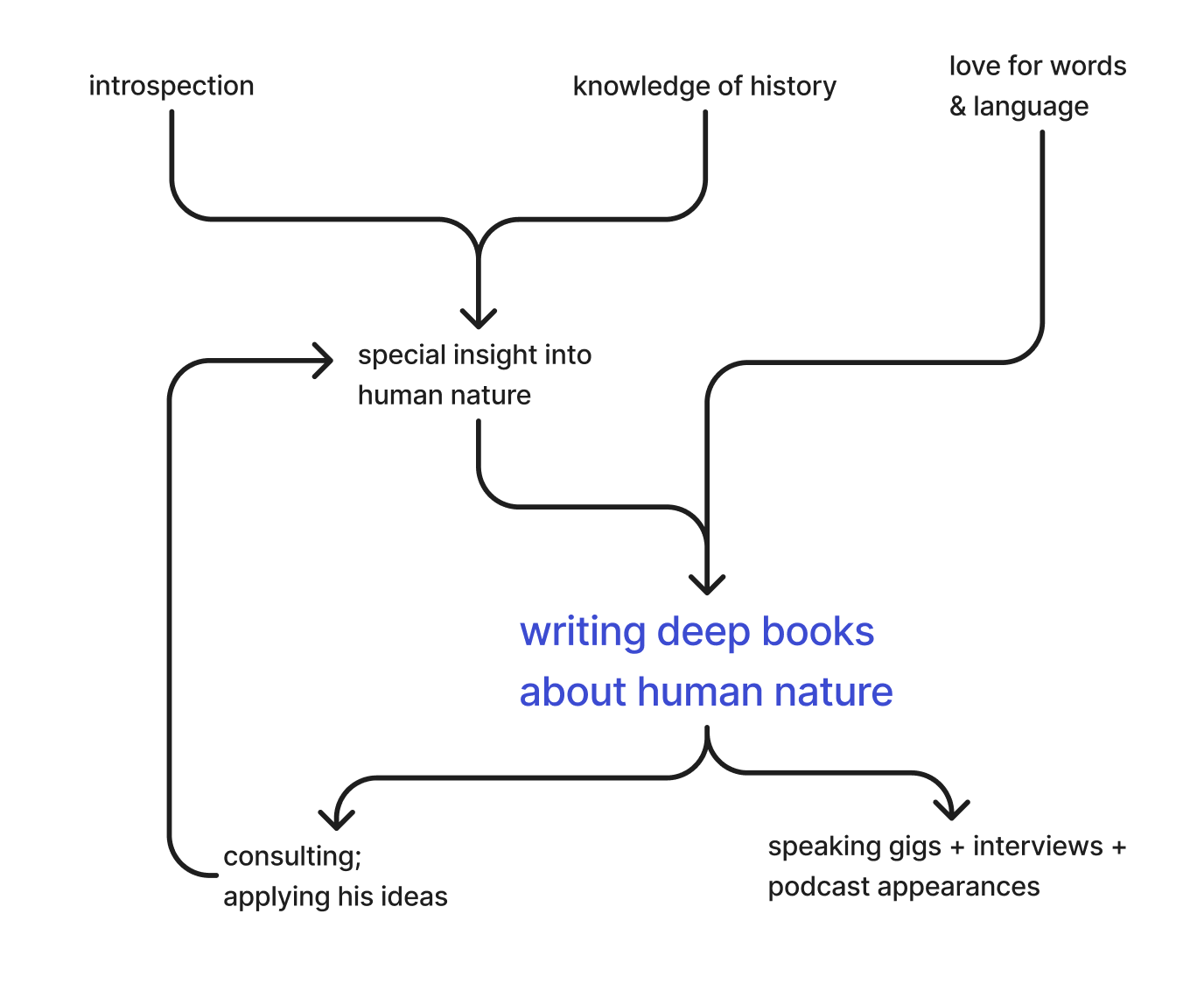

He’s a genius, and his flywheel reflects that: it includes his observational abilities, his love of words and language, and his encyclopaedic knowledge of history.

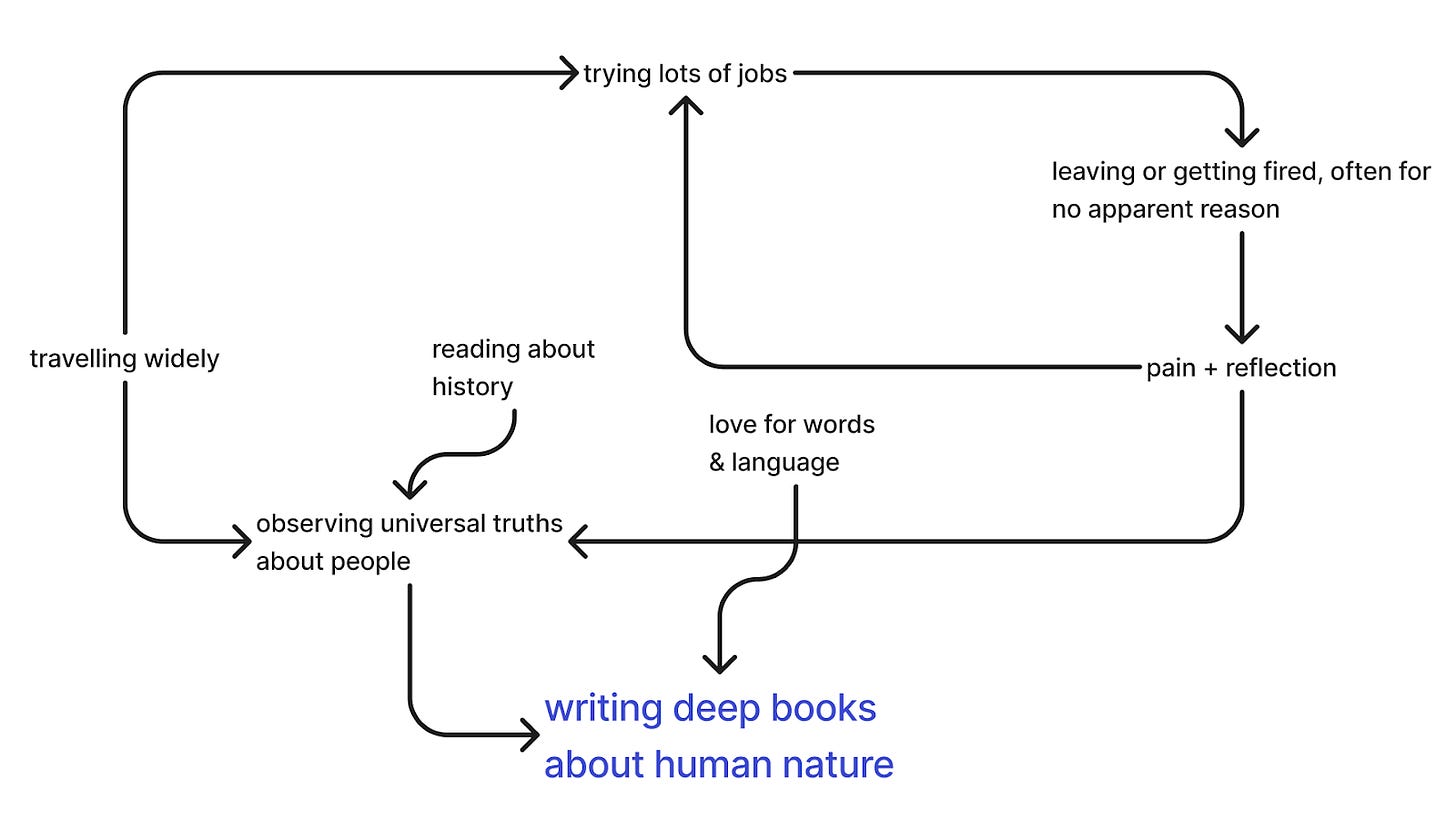

But he’s also human, and his flywheel reflects that too: Greene bounced between dozens of jobs for nearly 20 years (he started writing The 48 Laws of Power in his late thirties). He was fired, often for no apparent reason at all, and at times felt so lost that he’d succumb to depression. These aren’t merely obstacles he overcame – they were crucial components of Greene’s personal flywheel:

The accumulating advantages inherent to his personal flywheel – warts and all – eventually resulted in a singularly successful career, in which he leverages his personal traits and experiences to live his purpose (and make lots of money):

Robert Greene leveraged his literary skills and personal uniqueness. But he also channelled the particular pain he experienced – in his case, falling prey to the Machiavellian types around him – into powerful forces that drove his personal flywheel.

And he did this without knowing it: he was just trying to recover from the latest bruising.

He was unaware of the flywheel he was building. But in 1995, an acquaintance of his who worked in publishing asked if he had an idea for a book. Scrambling, he came up with an impromptu proposal. This proposal – the sum of his victories and his foibles – became The 48 Laws of Power, which sold over 1 million copies.

How to Find The Flywheel of You

So if you’re struggling to find your purpose, don’t fret. Here are three steps you can try:

Decide

Decide that you want to make the most of your life by finding your flywheel. Desire is the force that will fuel your flywheel.

Detach

Detach yourself from the outcome. This is the paradox of non-attachment – you must want things badly, and act to attain them, but be willing to not have them.

The reason that detachment is crucial is because, without it, you will constrain your search to patterns that seem virtuous. If you’re Robert Greene, you might note your penchant for writing, while mistakenly ignoring all of the valuable insight about human nature you’re gaining through your ugly career failures.

Or take me – I’m a tracker. I love to measure and catalogue things. I’ve taken notes on dozens of articles, interviews, and books – just for fun. For two years, I maintained a spreadsheet tracking how I spent my time in a failed effort to be more productive. These habits have no obvious economic value. But I’m drawn to these unique behaviour patterns. If I’m sufficiently detached, my subconscious filters won’t ignore opportunities that leverage such quirks.

Detect

Observe yourself carefully. Pay attention to the things you habitually do. You can even do this retrospectively, using your mind’s eye to return to your childhood and remembering what drew you in as a child, when you were most authentic.

I can’t emphasise enough that what you perceive as a vice (watching too much TV) can actually be a strength (Packy McCormick littered early editions of his business newsletter with pop culture references, distinguishing his voice and building a following of ~150,000 subscribers). Don’t exclude something just because it’s mundane or – in your view – unlikely to be useful.

So relax. Exhale. There’s nothing wrong with you. And if there is – there might just be a way to leverage that.

this shit is liquid fire

I think another way to say this is that famous Steve Jobs quote: "You can only connect the dots looking back"